My creative background has intersected jazz with photography. The two artistic endeavors are eerily similar. Jazz and Photography continues to play important roles in my life and in so many others.

Whether good or bad, we photographers always are searching for perfection. We sometimes, to our detriment always seek to be at just the right place, at the just the right time, and to depress that shutter button at precisely just the correct moment. We are often way too consumed in trying to depict the scene at its very best in the so called “perfect light”. To complicate matters, at the very same time, we are evaluating (many times over-evaluating) our technical settings such as aperture, depth of field, focus and more.

Whether good or bad, we photographers always are searching for perfection. We sometimes, to our detriment always seek to be at just the right place, at the just the right time, and to depress that shutter button at precisely just the correct moment. We are often way too consumed in trying to depict the scene at its very best in the so called “perfect light”. To complicate matters, at the very same time, we are evaluating (many times over-evaluating) our technical settings such as aperture, depth of field, focus and more.

I have been trained as a musician. I did a lot of things musically both structured and not so much. Musicians, like many photographers I know strive for perfection. Musicians have been trained to be concerned in playing the right note at the right pitch at the right time. This concept can work in negative ways.

As we know the brain is made up of two sides, the left and the right. We associate the left side of our brains as being the analytical side and the right as the creative side.

Jazz musicians, have adapted themselves to use both sides of their brains at once, a rather hard thing to do. Click HERE to read about this). I believe that photographers, who must frequently deal with outside influences such as changing light, weather conditions, and more, must act like a jazz musician, and learn to use both sides of their brains at once and improvise. It’s not easy. Let me explain.

At Johns Hopkins University, a team of doctors and government scientists conducted studies and discovered that when a jazz musician improvises, their brains turn off areas linked to self-censoring and inhibition and turn on those that let self-expression flow.

They have concluded that jazz musicians create their unique improvised “lines” by turning off inhibition and turning up creativity. I strongly suggest that photographers try to follow a similar path.

They have concluded that jazz musicians create their unique improvised “lines” by turning off inhibition and turning up creativity. I strongly suggest that photographers try to follow a similar path.

This joint research, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or FMRI, and musician volunteers from the Johns Hopkins University’s Peabody Institute, shed light on the creative improvisation that artists and non-artists use in everyday life.

First, being proficient on a musical instrument isn’t easy. For me it’s infinitely harder than taking a photograph. Becoming a good musician, let alone a jazz musician takes discipline and practice (sound familiar?) Now, apply this concept to photography and you are on the way to your creative awareness. When playing jazz, you not only need to play your instrument technically well, but at the very same time you are evaluating other things like song form, harmony, melody, dynamic range, what the rest of the group is doing and more, all while playing your instrument or singing. When we are using our cameras, we are basically striving to do the same thing and adapt to the environment which is usually changing. In other words, in the ever-changing field, nature photographers too are improvising, sometimes not realizing it. Over ten years ago I wrote an article on the importance of knowing and being technically proficient with your camera, just as I learned to know and be proficient my musical instrument. Functionality needs to be second nature to allow us to concentrate on the creative side of our mission. Check out that article HERE

Being a good musician on any instrument or voice is tough. A lot goes into it. Believe me, playing jazz really isn’t easy as there is much more involved than just playing some notes on the paper. As well and as many of us have learned, making a creative and interesting image is also tough. Frankly, anything aspect of art, to do it at a high level is hard.

Being a good musician on any instrument or voice is tough. A lot goes into it. Believe me, playing jazz really isn’t easy as there is much more involved than just playing some notes on the paper. As well and as many of us have learned, making a creative and interesting image is also tough. Frankly, anything aspect of art, to do it at a high level is hard.

Jazz is often described as being an extremely individualistic art form. A trained jazz aficionado can tell one musician from another because their playing or improvising sounds only like him or her. As Charles J. Lamb, M.D., assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a trained jazz saxophonist himself said, “It’s a remarkable frame of mind, during which, suddenly, the musician is generating music that has never been heard, thought, practiced, or played before. What comes out is completely spontaneous.” I say, why not apply this same principle to photography?

It has also been found the brains of classical and jazz (I really dislike those terms!) musicians work differently. A study published by the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive Brain Sciences found that jazz musicians (based on improvising) and classical musicians (based on reading notes and other instructions on a sheet of music) demonstrate quite different brain activity, even when playing the same music. You can access the study HERE.

Classical musicians concentrate on the “HOW” while jazz musicians focus on the “WHAT”, meaning that jazz musicians are always ready to improvise and adapt to the notes they are playing. I contend that a nature photographer should go about making images more like the jazz musician. We should be thinking about “WHAT” more than “HOW”

One of my favorite jazz pianists Keith Jarrett was asked if he would like to do a concert featuring both Jazz and classical music. He ardently said “NO, that’s hilarious! It’s because of the circuitry. Your system demands different circuitry for either of those two things.”

Embrace the Moment

We often get caught up in the moment, especially when things are changing, I’ve written about being prepared and the downside of being over prepared. (Click HERE for this article).

Some of the best jazz ever created was done in spontaneity. Miles Davis recorded an album in 1959 called Kind of Blue. It has sold over 4 million copies, more than any other jazz album. To no ones surprise, the first day ( this record was made in only two days of recording and just a few takes of each tune) of the recording session, Miles showed up with only a few notes on a sheet of paper, no score and certainly not large book of compositions. As Miles said “I didn’t write out the music for Kind of Blue, but brought sketches, because I wanted a lot of spontaneity in the playing. I knew that if you’ve got some great musicians, they will deal with the situation and play beyond what is there and above where they think they can”

Some of the best jazz ever created was done in spontaneity. Miles Davis recorded an album in 1959 called Kind of Blue. It has sold over 4 million copies, more than any other jazz album. To no ones surprise, the first day ( this record was made in only two days of recording and just a few takes of each tune) of the recording session, Miles showed up with only a few notes on a sheet of paper, no score and certainly not large book of compositions. As Miles said “I didn’t write out the music for Kind of Blue, but brought sketches, because I wanted a lot of spontaneity in the playing. I knew that if you’ve got some great musicians, they will deal with the situation and play beyond what is there and above where they think they can”

I can guarantee that if we look back at some of our best images of all time, most were taken using the same spontaneity as Miles used, seized the moment and adapting our visual world to fit what we were trying to convey through the lens at the time.

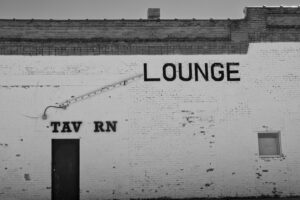

As photographers I suggest we embrace the times when things don’t go as expected and improvise. Make sense of what is in front of you and seize the opportunities. I do not get concerned about what happens when the magic doesn’t appear, or it disappears while I am getting my gear together. Look around for new things to photograph and welcome the challenges that so often are part of being a photographer. This might be the time for something different. Most of the photographers that we look up to do things different, see things differently, and most important are true to themselves. Accomplished jazz musician do the same every time they play.

Final Thoughts

As a musician, I learned to play in tune, follow form, control dynamics, and communicate a story using the notes of the music. I also learned to play (improvise) using all that I have previously stated to tell my story through notes, textures, dynamics, phrasing etc. Think of a landscape as a sheet of music. A successful photographer must choose things like including or excluding movement, brightness and shading and more to communicate their vision within the frame (form) and tell their individual story using the contents of the frame, no more, no less.

As a musician, I learned to play in tune, follow form, control dynamics, and communicate a story using the notes of the music. I also learned to play (improvise) using all that I have previously stated to tell my story through notes, textures, dynamics, phrasing etc. Think of a landscape as a sheet of music. A successful photographer must choose things like including or excluding movement, brightness and shading and more to communicate their vision within the frame (form) and tell their individual story using the contents of the frame, no more, no less.

Deciding on what priority to use, what ISO, what aperture, what focal length to use is no different from a musician making the decision on how fast or slow to play, how loud or soft to play or what feeling they would like to portray.

It is also to your advantage to lose any inhibition and make images for yourself, not worrying about how your piers on social media or your friends will think about them. Photograph for you. In other words forget the critic! Turn up your creativity. This almost always happens when musicians improvise.

Those of us who have been seeking to grow creatively as a photographer have, for many years, been on the same path as that jazz musician. The camera is your instrument. Learn it, practice it. Know where all the buttons and dials are Your left side of your brain will take care of that. Learn to worry about the right side, your creative side. Learn to improvise using your camera and lens., especially when things are changing. That is the hard part. Being both technical and creative is very difficult, but is certainly possible. Many have already accomplished this photographically.

It’s interesting to me how many musicians have become good photographers. HERE are just a few. Milt Hinton, one of the greatest bass players was an accomplished photographer. I was fortunate to have done a few dates with him. Ansel Adams though not a “jazz” player, was an accomplished pianist. Here is a direct quite from Ansel about how music framed his life. When asked if music was the first thing that gave him order in his life, Adams responded, “Yes. I had an extraordinarily piano teacher. He knew nothing of contemporary psychology, just sent me home time after time with Bach’s “Invention No. 1” until I knew the notes. Theoretically, that should have completely shattered me and put me in the loony house, but it saved me”. Adams then stated “Study in music gave me a fine basis for the discipline of photography. I’d have been a real Sloppy Joe if I hadn’t had that.” Elaborating further, he added, “Well, in music you have this absolutely necessary discipline from the very beginning, and you are constructing various shapes and controlling values. Your notes have to be accurate or else there’s no use playing. There’s no casual approximation.”

Adams stated that he would often hear music while photographing. “You see relationships of shapes. I would call it a design sense. It’s the beginning of seeing what the photograph is.”

Adams stated that he would often hear music while photographing. “You see relationships of shapes. I would call it a design sense. It’s the beginning of seeing what the photograph is.”

It’s not an accident. Yes, it’s hard. That is also why there are few like Louis Armstrong’s, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker, to name a few. That is also why there are few like Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Galen Rowell to name only a few.

Images and text ©Jack Graham /Jack Graham Photography. All Rights Reserved

As Bill would say, “Love, love, love” this article. Excellent, Jack. Much food for thought. I love that you mentioned Galen Rowell and I’m sure you know that his mother was an internationally acclaimed cellist, but your audience may not know. I’m sure living with a musician such as she was and having musicians in and out of the house continually impressed on Galen a quest for achievement that he might not have had without it.